The turbulent 60s are remembered for acid trips, antiwar protests, voyages to the moon and "I Dream of Jeannie." But the 60s were funny—they also gave us the AFL and Spiro Agnew, Nancy Sinatra and the Silent Majority. When you look for the Sixties, you find as much Perry Como as you do the Electric Prunes.

OK, you say, that's easy. There's a counter counter-culture—so what? Well, to really get the 60s, and thus understand the inside-out nature of the human condition, you have to pour some mainstream into the counter-culture to give it legitimacy; then you also have to groom and button-down the counter-culture, that others might listen.

The 60s did just that. Dirty, smelly hippies tended to come from middle-class homes, while fat-cat Republicans appealed to working-class shmoes by insisting on the law and order that arrested working-class shmoes and undermined their economic security. But it's easier to look ata folk music as an example, which had a clear political message, within a simple structure, geared toward the everyday fellow with bills to pay. By the 60s, folk music had reached urban areas from farms, work camps and boxcars. Its message of individual dignity in the face of official violence got the attention of intellectuals, who began morphing songs within its simple form about negotiating the anonymity of modern life. But these hipsters were pre-hair: the look was totally mainstream with an informal college bent. After the Beatles, 60s hair arrived and Folk followed along. Plus, Bob Dylan had led the form away from "Tom Dooley" toward "A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall." Beatles + Dylan = The Byrds, 1965. Eventually, it reduced to the single, singer-songwriter whose selling power dominated the 70s.

By the 60s, folk music had reached urban areas from farms, work camps and boxcars. Its message of individual dignity in the face of official violence got the attention of intellectuals, who began morphing songs within its simple form about negotiating the anonymity of modern life. But these hipsters were pre-hair: the look was totally mainstream with an informal college bent. After the Beatles, 60s hair arrived and Folk followed along. Plus, Bob Dylan had led the form away from "Tom Dooley" toward "A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall." Beatles + Dylan = The Byrds, 1965. Eventually, it reduced to the single, singer-songwriter whose selling power dominated the 70s.

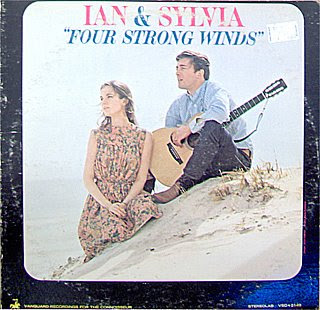

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Folk was at its height in the early 60s before it melded with other pop strains to become The Mamas and the Papas. One such act was the duo Ian & Sylvia. They interspersed their own songs with traditional and standard songs from Folk's "catalog." Their voices worked nicely together, although Ian's was primary. What I find most interesting, and what Ian & Sylvia display, is the trained-voice style of singing you hear in Folk. If Ella Fitzgerald sang Folk, it would be usual for the form. Cripes, there are times when Ian sounds like Al Alberts, likely the most unpleasant singer of all time. Listen to another awful singer, Joan Baez: someone get that vibrato a drink, already! This is how Folk, while targeting its message to the exploitative heart of Western culture, is expressed in the same bougeois musical style as gave us Al Jolson (bad) and Tony Bennett (good). Dylan is teased mercilessly for his voice, but he was the god who freed us from that fatal Folk flaw.

Folkies, like most early Rock-era groups, wore suits and ties. Pretty much everyone did before the 70s, so when you combine a progressive message with status quo delivery, you have an inherent tension between meanings. Competing messages. It could only be resolved through rationalization, especially when the message wasn't completely formed, let alone understood. Folk lost and had to re-form as pop.

But that progressive message was still there and the understanding was indeed coming along at a nice pace. While songs about unionizing coal miners really did coincide with the emptiness of life in a gray flannel suit, it took the specter of annihilation and the murder of a President to clarify the fiction of most people's lives. So as Folk took a hiatus for several years, it was up to others to renew or repeat the simple lessons Folk offerd us. Dylan was still around and the Beatles tried to be relevant, but it was more mainstream guys who asked the tough questions: The Beach Boys, Johnny Rivers and yes—even Johnny Cash. And Ed Ames. A rich baritone from the Ames Brothers and his own solo success, Ames went looking for the sharp new material that was changing Mom & Dad's records. New songs from the likes of Neil Diamond, Jimmy Webb and Burt Bacharach had made superstars of the artists who performed them. It was a new era for the Brylcream set, away from standards and toward contemporary relevance. It was think or swim for Adult Contemporary.

And Ed Ames. A rich baritone from the Ames Brothers and his own solo success, Ames went looking for the sharp new material that was changing Mom & Dad's records. New songs from the likes of Neil Diamond, Jimmy Webb and Burt Bacharach had made superstars of the artists who performed them. It was a new era for the Brylcream set, away from standards and toward contemporary relevance. It was think or swim for Adult Contemporary.

Ames took a risk and released "Who Will Answer?" in 1968, with tunes by Dylan, the Beatles, the Bee Gees (pre-Disco), the Mamas and the Papas, The Monkees, the Association and Petula Clark. The title track made the top 10 on Adult Contemporary charts, and even cracked the top 20 in Pop one week. "Who Will Answer?" is maybe that moment when Folk was able to reach people who weren't generally interested in social progress, but could stand to gain from it; and where Mainstreamers widened their record collections a little past Sinatra and Herb Alpert and extended a hand to Freedom Marchers from the backyard bar-b-que.

But it didn't last, even if there was such a moment, really. In 1968, Rock went into hyperspace, angrily leaving behind any mainstream pretensions. Society engaged in actual street battles and social progress was identified with trouble makers, labeled as radical. The Mainstream plugged its ears amd closed ranks. Idealism was sent to jail or shot dead outright, but everyone grew lots of facial hair as a consolation prize.

Any idealism of the 60s gave way to merchandising and malaise. Baby Boomers gave their fringed suede coats to Goodwill and went to business school adter Nixon resigned, content to have fallen Presidents as bookends to their decade of easier sex disguised as a new mentality. Unable to recocile neckties with songs about hoboes, Folk had earlier ratioanalized itself by appealing to parents. Mainstream music had needed brainy new music to survive, and it too rationalized itself by buying off songwriters and dressing the artists more casually. Music stood to bridge divides for a moment, but ended up as simple entertainment, with common points of rference, for different groups locked in conflict.

Everybody lost. That is the most apt summation of the 60s.

July 28, 2008

Song of the 60s

Labels:

1968,

60s,

Ames Brothers,

Bob Dylan,

Ed Ames,

Electric Prunes,

Folk music,

Ian and Sylvia,

JFK,

Joan Baez,

Nixon,

Silent Majority

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment