Recently, I chanced to watch a couple movies that I can't help juxtaposing. I find acting has changed in the past 40 years, and that's a good thing.

Recently, I chanced to watch a couple movies that I can't help juxtaposing. I find acting has changed in the past 40 years, and that's a good thing.

Acting, I adjudge, is the intermediary conveyance of cultural messages to an expansive audience. Actors do not merely address the mob with some opinion. They address the audience as the personification of a complex of symbols that resonate with the experiences of the audience. Hence, the opinion of the maker of the words that an actor speaks becomes a reality that commands reaction.

But you knew that. Acting was invented by ancient people who had little to do when the sun set. After a while, star gazing and interpretation get boring, then singing gets old until you get new songs. Enter the actor, who spins tales of mythical exploits and creates characters that actually come to life at fireside. From there, audiences are captivated as the actor brings to life the creatures and situations of their imaginations.

Acting was invented by ancient people who had little to do when the sun set. After a while, star gazing and interpretation get boring, then singing gets old until you get new songs. Enter the actor, who spins tales of mythical exploits and creates characters that actually come to life at fireside. From there, audiences are captivated as the actor brings to life the creatures and situations of their imaginations. Fast forward 3,000 years. You have the theatre at it's height by mid-twentieth century: the technology, the real estate, tectonic social and cultural shifts... It's all there and actors help us cope. But it's the traditions of theatre that actors brought to film—the booming voice and exaggerated movements—and expectedly so. These were developed to reach the furthermost seats, high and away, from the stage. It becomes part of the craft of acting, to be boldly subtle, subtly bold. What I just can't figure is why it took so long for actors to develop a film craft.

Fast forward 3,000 years. You have the theatre at it's height by mid-twentieth century: the technology, the real estate, tectonic social and cultural shifts... It's all there and actors help us cope. But it's the traditions of theatre that actors brought to film—the booming voice and exaggerated movements—and expectedly so. These were developed to reach the furthermost seats, high and away, from the stage. It becomes part of the craft of acting, to be boldly subtle, subtly bold. What I just can't figure is why it took so long for actors to develop a film craft.

Watch movies before the 1960s and you see the stage recreated without the audience. Bette Davis bellows, Charles Laughton poses and accents, Jennifer Jones verges on neurosis. The exceptions are the greats: Crawford's look freezes the viewer, Grant's charm moves his conversation. But even with these, guys like Gregory Peck act some poor role into the ground, and Taylor and Burton seethe beyond repair.

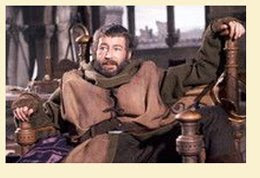

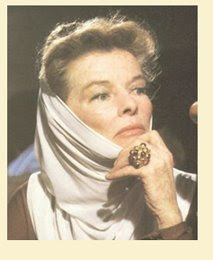

It's as if we don't have microphones and the close up. Why do they go so far? Because they're actors, that's why. And Peter O'Toole bellows. OK, it's 1968 and "The Lion in Winter" is released. It was a play adapted for the screen, meaning it was shot outside. But we get theatrics just the same, and two Actors' Actors will give us the thrill of the theatrical experience. In "Lion," O'Toole plays every scene hollering. I mean it, every one. Nigel Terry and Timothy Dalton play every scene as if they're onstage, with hyper-crisp diction and the poetic gestures of true Thespian-ity. Hepburn, John Castle and Anthony Hopkins, meanwhile, understated their performances to the cool eye and ear of the filming process. The difference in performances is so very obvious.

And Peter O'Toole bellows. OK, it's 1968 and "The Lion in Winter" is released. It was a play adapted for the screen, meaning it was shot outside. But we get theatrics just the same, and two Actors' Actors will give us the thrill of the theatrical experience. In "Lion," O'Toole plays every scene hollering. I mean it, every one. Nigel Terry and Timothy Dalton play every scene as if they're onstage, with hyper-crisp diction and the poetic gestures of true Thespian-ity. Hepburn, John Castle and Anthony Hopkins, meanwhile, understated their performances to the cool eye and ear of the filming process. The difference in performances is so very obvious.

To be fair, "Lion" is a play, and they hired Actors first, Movie Stars second. Also, BIG in 1968 still meant theatrical. Moreover, Director Anthony Harvey had no interest in the subleties of film: he did a bunch of Hepburn pictures, and he was probably her choice. She does, after all, come out as the top presence in the film and she won an Academy Award for the role.

In "Lawrence of Arabia," O'Toole was the very conscience of film. He was handsome, moved with grace, spoke beautifully. Same in  "The Last Emperor." But under the misguided direction of Harvey's rococco tastes, O'Toole is like a drunken Burton—show up, yell your head off, go home.

"The Last Emperor." But under the misguided direction of Harvey's rococco tastes, O'Toole is like a drunken Burton—show up, yell your head off, go home.

Hepburn played theatrical-type farces in the '30s with a real understatement, as if she "got" movies where others might not. Onstage, too, she had a reputation for being able to whisper to the back row. She was an actor. And Harvey let her do her stuff in the film, with tears and laughter as real as the cold of the English outdoors.

The film really misses after 40 years because it's so darn corny. And it's  because all that acting going on veers us away from the complexity of the story: gender and what it means to be man and / or woman; how power corrupts the individual; the price of work and money on family and self; class, caste and status... All this stuff is open in the play but nearly chucked in the film, almost as Henry discards his relationships.

because all that acting going on veers us away from the complexity of the story: gender and what it means to be man and / or woman; how power corrupts the individual; the price of work and money on family and self; class, caste and status... All this stuff is open in the play but nearly chucked in the film, almost as Henry discards his relationships. Now, let's get to 2005 and "{Proof}". Here, you have modern actors whose characters live onscreen. Jake Gyllenhall and Gwyneth Paltrow make movies and understand the subtleties of movement, the photographer's art and the priceless effect of naturlness. When they argue, they portray the dynamics of an argument—sometimes loud. But they do not holler as if they are onstage. Now, "{Proof}" was also a play and it's likely the actors had to do that stage voice modulation—yell—because it's theater. But in the film, it's all at room temperature, shall we say. The actors imbue characters with life actually lived, photographed for us. The resonate with our experiences of the audience; the words the actors speak become a reality that commands our reaction.

Now, let's get to 2005 and "{Proof}". Here, you have modern actors whose characters live onscreen. Jake Gyllenhall and Gwyneth Paltrow make movies and understand the subtleties of movement, the photographer's art and the priceless effect of naturlness. When they argue, they portray the dynamics of an argument—sometimes loud. But they do not holler as if they are onstage. Now, "{Proof}" was also a play and it's likely the actors had to do that stage voice modulation—yell—because it's theater. But in the film, it's all at room temperature, shall we say. The actors imbue characters with life actually lived, photographed for us. The resonate with our experiences of the audience; the words the actors speak become a reality that commands our reaction.

The complexity of the story is central and we don't lose it to some hollerer's genius, or something. The effect of death in the family on its members; the delicate psyche and its relationship to creative greatness; gender and success; the receptiveness of institutions to individual breakthrough... "{Proof}" has all this and it's the very purpose of the film. So you have "The Lion in Winter" spoiled by an undisciplined exercise of the craft, and "{Proof}" heightened by the proper employment of it. While both movies have merit, one stands out by delivering the essence of the work. The other obscures it (not entirely, mind you), enough to sully the importance of the actor by acting too hard.

So you have "The Lion in Winter" spoiled by an undisciplined exercise of the craft, and "{Proof}" heightened by the proper employment of it. While both movies have merit, one stands out by delivering the essence of the work. The other obscures it (not entirely, mind you), enough to sully the importance of the actor by acting too hard.

No comments:

Post a Comment